remembering a poet of crianza / the gift of nurturance

Kenneth Patchen was a powerful working class poet from Ohio, USA. He wrote some of the strongest anti-war poetry alongside some of the most tender love poems. He laid some of the the groundwork for the Beats by reading poems with the jazz musician Charles Mingus accompanying him on upright bass. He fought long and hard with his words, all of which were acts of defense; the defense of dignity, tenderness, nurturance, truth, and beauty, all in the face of the horrors of history. He wrote his poetry and prose through the two World Wars, and never lost sight of the human heart and the natural world, of the importance of communion and conversation, of resistance and regeneration. Patchen wrote, "Gentle and giving- the rest is nonsense and treason."

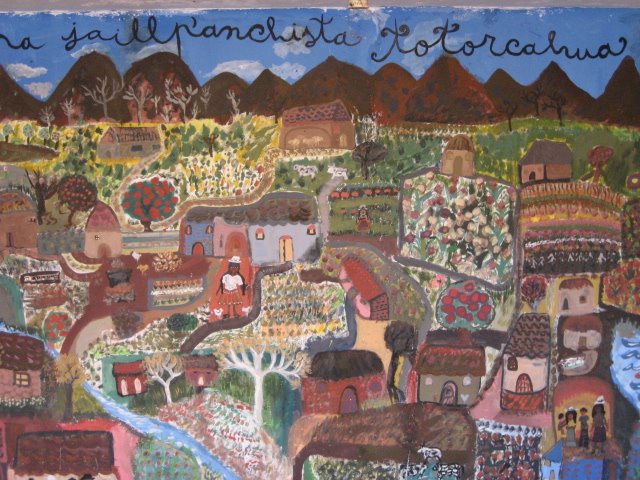

Becoming rooted in the village of Totorkawa (Cochabamba, Bolivia), I've metaphorically kept that phrase tucked in my ch'uspa, along with coca leaves, and sometimes a little tobacco. I recall fondly an interaction I had upon first moving here with my wife Valentina, an embodiment of that phrase (which i've come to refer to as an ethic of crianza; nurturance in Spanish). I was introduced to a lumberjack/farmer in a neighbors' dirt floor courtyard where people come together to drink and share the fermented corn beverage called chicha. This man embraced me and said something along the lines of, "My friend, there are no strangers here. It is all about friendship, and nurturance." I see this gentleman frequently but still don't know his name ( often triggering further reflections upon what it really means to be a gentle man). I call him maestro, and he greets me with a tip of his hat and an "hola hermano!". Sometimes he even kisses the knuckles of one of my hands. It was a profoundly moving moment for one such as myself; a survivor of the U.S., which often seems to be the polar opposite of such warm, human values/principles, ethics. The very word nurturance has even fallen out of use, damn near disappearing altogether. When I talk to folks about our work back in Totorkawa in the learning community of UywanaWasi (La Casa de la Crianza), there is usually an uncomfortable silence when I translate crianza into nurturance. In certain moments, time allowing, the pause becomes an inroad for having a deeper conversation about how that ethic manifests itself in Andean culture, and what it might look like locally if we recuperated and placed at the very center of our beings and communities such an ethic. In the book The Unsettling of America the Kentucky poet/farmer/philosopher Wendell Berry wrote, thirty years ago, about the dominant culture of exploitation and the threatened culture of nurturance, of how these two mind sets are present within everyone.

I write this while back in southern Appalachia, where the culture of exploitation has reached horrifying new levels, in the guise of mountaintop removal, and the appearance of "supermax", for -profit prisons. There is still, fortunately, a cultural thread running through the land here that is a thread of nurturance. It manifests itself in home cooked meals, sitting on the front porch and conversing with friends and neighbors, playing music, tending a backyard garden of tomatoes, beans, okra, corn. Lots of young radical activists these days are locking themselves to the entrance gates of coal plants, to tractors and trucks, dropping banners that name the injustices and its collaborators. Rightly so. But if those faint and fragile threads of communion and regeneration continue to wither, if they are not affirmed, practiced, kept front and center in our lives, the laundry list of indignities will become so overbearing that we may ultimately find ourselves in an existential briar patch, whereupon every activist type lunge at "the problem" tears at us and draws a bit more blood. We may end up solely residing in a state of indignation ( a barren land of countless indignities); knocked off center by righteous anger, no longer able to be "gentle", "giving", unconsciously contributing to the death of nurturance.

My sons Camay and Samiri accompany me most mornings, out towards the far side of one of our chacritas (in the Andean cosmovision, the plot of land where the human community, the community of dieties, and the natural world converse), to warm our bones in the first rays of sunlight. Sometimes Samiri, two and a half, wanders over to nibble on some fresh spinach leaves or crunch on a string bean. Camay, going on seven, in those moments sometimes busies himself gathering up some lemons and apples from the trees that ring the chacra, to take down the road to share with his friends. They start their day nestled safely within a cultural hammock where crianza, nurturance, still holds sway. I'm careful not to idealize or romanticize here. Forces of modernity and progress are weighing down upon our village every day, as they do upon thousands of other villages across the "global south". Sometimes one can almost hear a "snap!" in the wind as the illusions of modernity seduce (trick!) folks into venturing into the city to sell their labor on the cold and inhuman free market. There is much confusion and ensuing violence; directed toward the self, others, sometimes the land and fellow creatures. The violence I believe comes when we feel the scales being tipped, when exploitation is held in high esteem and nurturance viewed as child-like, as a thing of the past, an impediment to "progress" even! It becomes more explosive when we find ourselves unable to name, to define clearly, this grave imbalance and to understand its roots.

Sometimes, as a younger man, I had a recurring dream of being up in the branches of a tree. Each branch stood before me as a person in my life. If I let my gaze trail down one particular branch, I usually , very quickly, arrived at the realization that there was a crippling pain killing that branch. The dreams have stopped in direct correlation to a growing commitment to get at the roots of all this pain, and to become a farmer, and a "poet of crianza". The late Eduardo Grillo (and his companeros), of the Peruvian learning community PRATEC, frequently uttered this phrase: "Criar y dejarse criar". Nurture and allow oneself to be nurtured. I added it to my ch'uspa, where it nestled naturally beside the phrase from Kenneth Patchen. While chewing a little coca, our boys playing at my feet, I penned this tune, "You're Not Broken".

-*-

A jar o´shine by my side

And fiddle tunes on the wind they do ride

And they tell me somethin´ I once did know

They remind me of somethin´ I once did know

Boy, you´re a child of the Blues, God, and ol´ Mother Earth

& spirits gathered ´round at the time of your birth

I recall the day like so many ones before

But it´s easy to forget here on the killin´ floor

You´re a poet, a father, a farmin' man

A rebel, a race traitor, an American

Borders will not hold you nor no silly little flag

Nor no party allegaince or a stupid little tag

You´re a miner of truth & a laborer of love

Communin´with nature and the spirits above

You´re not broken though society´ll try like hell

You´re not broken, go on boy, I wish you well

A candle sits on a shelf in the hall

Step out on the front porch & hear them night birds call

And they tell me somethin´ I once did know

They remind me of somethin´ I once did know

Ssshh, lissen´up, step inside the wind

Life is love and death your friend

Morning glories open, close, climb & fall

Corn spires, cook fires, and childrens´calls

Sayin´, “Hey Mister, ´Scuse me Ma´am,

Won´t ya drop down on one knee & help us understand”

“All those hateful somethings you´re a-takin´ to your grave

Try takin´a nothin´you love...they call that gettin´ saved”

“But not by no hustler with a bible & a billfold in his hand

Ya see the Holy Ghost don´t need no middle man”

“`Gentle & Giving´ is what it´s all about

`The rest is nonsense & treason´ do I have to shout, do I have to shout!?!”

Jack Herranen