Thursday, August 2, 2007

Re-thinking Poverty

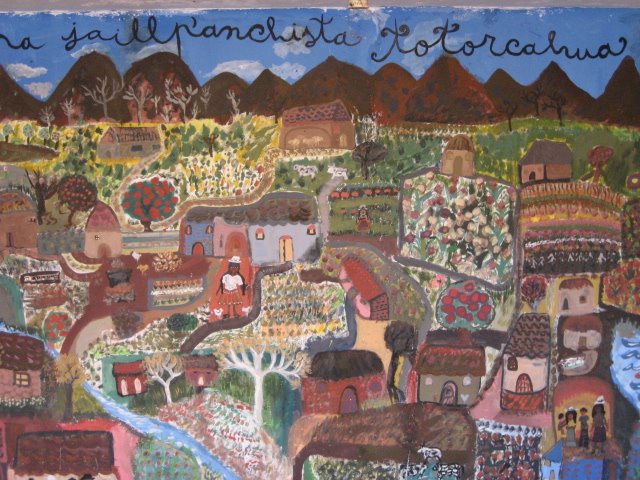

One of the greatest challenges in my adult life-as an artist,

activist, and son of southern Appalachia- has been the experience of

growing into the life of a rural farming village in the foothills of

the Bolivian Andes and the ways in which I've had to radically rethink

the very notion of "poverty". From UN reports to leftist journalism,

Bolivia is almost always described as "a dirt poor, landlocked,

primarily indigenous country in South America". Yet when I walk down

to my friend don Ramiro's house to pick up my son Camilo, after a day

of playing with his nine kids, I oftentimes literally feel giddy due

to the abundance and sense of generosity surrounding me. Any

well-intentioned development specialist would look out upon our

village and think, "How can we elevate these poor people out of their

stagnant and regressive lives?". I've learned to ask (myself first and

now others),'What Western myths need to be debunked to affirm the

dignified life here[in Totorkawa]?" Interrogating the confused Western

notion of "poverty", the lynchpin of the whole Western development

discourse, lies before me as a central task in the collective struggle

to recuperate human dignity.

Every day I interact with people here in East Tennessee who lead an

extremely impoverished existence, yet are swimming in goods, services,

modern amenities, and technological trinkets of all sorts. It could

be more precisely, responsibly, defined as "scarcity" although the

application of this term seems misplaced at first. When walking down

any one aisle at a typical grocery store in the United States,

"scarcity" may be the last word that comes to mind. One's thinking

gets jarred when striving to illuminate and understand all of the

subtle aspects residing within the blanket term "poverty". In the

chapter titled "Production" , in The Development Dictionary (Zed

Books, 1992), Jean Robert offers this insight into the violence and

degradation residing within these subtleties :

"Perhaps the modern economy is essentially a way of organizing reality

in a way that actually transforms both people and nature into waste.

For modern production to function, the economy must first establish a

system in which people become dependent upon goods and services

produced for them; and to do this, it must devalue historically

determined patterns of subsisting and corrupt cultural webs of

meaning. The mass production of modern goods, services and images

demands cultural blight through the spread of disvalue, that is, the

systematic devaluation of the goods found in traditional cultures.

Disvalue, to the extent that the economy is productive, entails a

degradation which touches everything and everyone affected by or

involved with this modern mode of organizing reality. A person is less

a person, the more he or she is immersed in the economy. And less a

friend. Less a participant in leisure- that is, in culture. The air is

less pure, the wild places fewer, the soil less rich, the water less

sparkling."

Many would beg to differ with this viewpoint, that one's humanity is

eroded the more they become involved in the economy. As a matter of

fact, many would say that "the poor" will only be freed by lifting

them up out of their villages and placing them into the labor force.

Ask a Chinese miner, an unemployed Nigerian tapping oil pipelines

under the cover of night, or a southern Appalachian miner's son

clocking in for his shift as guard -"over-seeing" primarily

African-American and Latino men- at the new Supermax prison about the

"freedom" and "dignity" they've found in the global economy. Wolfgang

Sachs' (along with others such as Ashis Nandy and Ivan Illich)

disentangling of notions of scarcity, destitution, and frugality from

the blanket term of "poverty" can greatly assist in the recuperation

of our critical faculties inside of imperial strongholds. Below is a

segment from Sachs' writings that is helpful in getting out from

underneath the suffocating blanket term of "poverty". It is a grave

injustice to define a whole people, a whole country, as "dirt poor".

It is an imposition and a violent assumption that wounds everyone

involved. It behooves us, especially Westerners suffering through an

accelerated process of social and cultural degeneration (inextricably

linked to our widespread ecological degradation), to hold this notion

up to the light.

Jack Herranen

(August the 2nd, 2007- southern Appalachia)

"Poverty" - In Need Of A Few Distinctions

You can't measure wealth by cash alone

by Wolfgang Sachs

One of the articles in Exploring Our Interconnectedness (IC#34)

Winter 1993, Page 6

Copyright (c)1993, 1996 by Context Institute

Many in the West misjudge our planet's diverse peoples by comparing

them with northern European and North American cultures. The following

excerpt from the October-December 1992 issue of Edges, published by

the Canadian Institute of Cultural Affairs, points to the

often-overlooked quality of life in communities that have kept their

distance from the commodity economy.

I could have kicked myself afterwards. Yet my remark had seemed the

most natural thing on Earth at the time. It was six months after

Mexico City's catastrophic earthquake in 1985 and I had spent the

whole day walking around Tepito , a dilapidated quarter inhabited by

ordinary people but threatened by land speculators. I had expected

ruins and resignation, decay and squalor, but the visit had made me

think again: there was a proud neighborly spirit, vigorous building

activity, and a flourishing shadow economy. [For more on Tepito , see

IC #30].

But at the end of the day the remark slipped out: "It's all very well

but, when it comes down to it, these people are still terribly poor."

Promptly, one of my companions stiffened: " No somos pobres, somos

Tepitanos! " (We are not poor people, we are Tepitans ).

What a reprimand! I had to admit to myself in embarrassment that,

quite involuntarily, the cliches of development philosophy had

triggered my reaction.

"Poverty" on a global scale was discovered after World War II.

Whenever "poverty" was mentioned at all in the documents of the 1940s

and 1950s, it took the form of a measurement of per-capita income

whose significance rested on the fact that it lay ridiculously far

below the US standard.

Once the scale of incomes had been established, such different worlds

as those of the Zapotec people of Mexico, the Tuareg of North Africa,

and the Rajasthani of India could be classed together; a comparison to

the "rich" nations demanded relegating them to a position of almost

immeasurable inferiority. In this way, "poverty" was used to define

whole peoples, not according to what they are and want to be, but

according to what they lack.

This approach provided a justification for intervention; wherever low

income is the problem the only answer would be "economic development."

There was no mention of the idea that poverty might also result from

oppression and thus demand liberation. Or that a culture of

sufficiency might be essential for long-term survival. Or even less

that a culture might direct its energies toward spheres other than

economic ones.

Binary divisions, such as healthy/ill, normal/abnormal, or, more

pertinently, rich/poor, are like steamrollers of the mind; they level

a multiform world, flattening out that which does not fit. That

approach also fails to distinguish between frugality, destitution, and

scarcity.

Frugality is a mark of cultures free from the frenzy of accumulation.

In these cultures, the necessities of everyday life are mostly gained

through subsistence production. To our eyes, these people have rather

meager possessions - maybe a hut and some pots and a special Sunday

outfit - with money playing only a marginal role.

Instead of cash wealth, everyone usually has access to fields, rivers,

and woods, while kinship and community duties guarantee services that

elsewhere must be paid for in hard cash. Nobody goes hungry.

In a traditional Mexican village, for example, the private

accumulation of wealth results in social ostracism - prestige is

gained precisely by spending even small profits on good deeds for the

community. Such a lifestyle only turns into demeaning "poverty" when

under the pressure of an "accumulating" society.

Destitution, on the other hand, becomes rampant as soon as frugality

is deprived of its foundation - community ties, land, forest, and

water.

Scarcity derives from modernized poverty. It affects mostly urban

groups caught up in the money economy as workers and consumers whose

spending power is so low that they fall by the wayside. Their capacity

to achieve through their own efforts gradually fades, while at the

same time their desires, fueled by glimpses of high society, spiral

toward infinity. This scissor-like effect of want is what

characterizes modern poverty.

Until now, development politicians have viewed "poverty" as the

problem and "growth" as the solution. They have not yet admitted that

they have been largely working with a concept of poverty fashioned by

the experience of commodity-based need in the North. With the less

well-off Homo Economicus in mind, they have encouraged growth and

often produced destitution by bringing multifarious cultures of

frugality to ruin. The culture of growth can only be erected on the

ruins of frugality, and so destitution and dependence on commodities

are its price.

In societies that are not built on the compulsion to amass material

wealth, economic activity is not geared to slick zippy output. Rather,

economic activities - like choosing an occupation, cultivating the

land, or exchanging goods - are understood as ways of enacting that

particular social drama in which members of a community see themselves

as the actors. The economy is closely bound up with life, but it does

not stamp its rule and rhythms on the rest of society. Only in the

West does the economy dictate the drama and everyone's role in it.

It seems my friend from Tepito knew of this when he refused to be

labeled "poor." His honor was at stake; his pride too. He clung to his

Tepito form of sufficiency, perhaps sensing that without it there

loomed only destitution or never-ending scarcity. "

Tuesday, July 17, 2007

Reflections on Racism

REFLECTIONS ON RACISM

(mid July, 2007)There, unfortunately, exists very little interest in understanding the dominant vision of “progress” and “development”- the ways they are driving all of our increasing problems, especially in regards to racism- nor is there much desire or willingness to explore solutions to our social ills that may arise out of our immediate, local contexts, especially when all of our leaders/authorities are conditioned to seek the answers solely in “Western” thought structures. So the constructed beliefs and myths continue in a very effective manner, like the belief that the spirituality of the indigenous peoples was “assimilated” into Christianity, when in fact, from the very beginning, there was a natural inclination among the indigenous towards respect and recognition of the “Other”, as opposed to tolerance and assimilation.

Valentina Campos

Totorkawa-Cochabamba, Bolivia

(translated by Jack Herranen)

Thursday, July 12, 2007

Excerpt from an unfinished essay (7-12-07, Knoxville)

This essay was begun in the days following the deadly conflicts in the city of Cochabamba, between campesinos and members of the extremist (and inherently racist) civic committees who identify primarily with the lowland political and landholding "Eurocentric" elite. On the 11th of January, 2007, three people were killed and literally hundreds hospitalized with severe injuries. The conflicts were/are about race, class, land reform, indigenous sovereignty, the decolonization of Bolivia's constitution (the Constituent Assembly), and oil and gas resources. To put all this into context, please take a look at an article written by Boilivia-based Mexican journalist/activist Luis A. Gomez:

http://www.ubnoticias.org/en/article/the-nature-of-the-beast

More soon, from beneath the Killing Floor,

abrazos,

Jack

-*-

“ A true revolution of values will soon look uneasily on the glaring contrast of poverty and wealth. With righteous indignation, it will look across the seas and see individual capitalists of the West investing huge sums of money in Asia, Africa, and South America, only to take the profits out with no concern for the social betterment of the countries, and say: ‘This is not just’. It will look at our alliance with the landed gentry of

King

“Next to money and guns, the

Illich

We, as activists, as American “do-gooders”, mostly continue to compartmentalize our understandings of economic justice. In our decades-long efforts at dismantling racism and building class solidarity we rarely touch upon the fact that economic growth demands cultural uprootedness and the dis-value of vernacular, indigenous wisdom. Nor do we even come close to identifying that that uprootedness is what allows us to become economized, what forces us to become competitive, violent individuals, mere consumers; what Ivan Illich earlier referred to as Homo Economicus, later as Homo Miserabilis. I am not trying to be tricky or vague here. The industrial era has grossly crippled us. We are ensnared in the web of the market, the global economy, and have traded off our commitment to place for a truly dizzying array of goods and services. Economic growth cannot permit conflictive allegiances. So, we spin things by correlating “liberty” to the uninhibited acquisition of more comforts and luxuries, and then will send our sons to war to protect this “right”. We no longer know what the good life, la vida dulce, might look and feel like. There is no functioning social fabric where one experiences such intangibles as care, solidarity, reciprocity. All these acts have been transformed into commodities. We’ve been duped into thinking that cultural traditions, place-based wisdom, the holistic and harmonious, the small and simple, - manifestations of the indigenous, and the vernacular-are impediments to “progress”. There is a radical analysis shared by certain intellectuals and activists that, before certain nations’ began violent colonialist and imperialist expansion/ subjugation of "the other", their own citizenry had to be colonized mentally. Uprooted from the land; ties severed, allegiances subsumed, convinced that the land based practices and communal responsibility practiced by our relatives were backwards, embarrassing. We had to be “individualized”, reduced to the lowly titled of “consumer” and, every few years, “voters”. This is what it means to be “economized”.

We are in a minefield. There are craters all around us. Certain words and notions are grenades. Pick one up: “Progress”- bam! “Poverty”-boom! “Development”, “Modernity”, “consumer confidence”, “Production”, “Industrialization” “First World”, “Third World”, on and on. Could this cruelty-uprootedness, placelessness- that we are all being subjected to be the source of our ethnic, race, gender, and class violence, not even mentioning the most obvious; the violence wrought upon the earth!?! From southern

Let us be careful not to side with a mere illusion; “I’m on ‘freedom’ and ‘liberty’s’ side!”, I hear some growl. “I’m for ‘progress’, ‘development’, and ‘the end of poverty’ I hear the well-schooled argue. The great, almost-forgotten,

It almost doesn’t translate, this dignified life in the foothills of the

“they have clubbed us off the streets they are stronger

they are rich they hire and fire the politicians the newspaperedi-

tors the old judges the small men with reputations the collegepresidents

the wardheelers (listen businessmen collegepresidents judges

the uniforms the policecars the patrolwagons

all right you have won you will kill the brave men our

friends tonight

turned our language inside out who have taken the clean words our

fathers spoke and made them slimy and foul

their hired men sit on the judge’s bench they sit back with their

feet on the tables under the dome of the State House they are ignorant

of our beliefs they have the dollars the guns the armed forces the

powerplants

they have built the electricchair and hired the executioner to

throw the switch

all right we are two nations

-from the trilogy

John Dos Passos

Albert Camus wrote, in The Rebel , “Economics, in fact, coincides with pain and suffering in history.” In that same book he also wrote, “The myth of unlimited production brings war in its train as inevitably as clouds announce a storm.” Some say that when Jesus entered the temple to drive out the sullying presence of the moneylenders he wielded a whip. The severity of our current situation cannot be denied. I’m consciously calling upon our collective legacy of rebelliousness here. We can derive much strength from it. Hell, my great grandfather, Jacob Nisula, was a Wobbly. As a young Finnish immigrant arriving through Ellis Island, he ended up in near indentured servitude in the silver mines of

The lines in the sand are abysses really. When we peer down into them we’re often frightened stiff by a sense of vertigo. Though if we are genuinely committed to a larger struggle for liberation and the recuperation of dignity we must not only look unwaveringly into them. We must, in a sense, rappel down into them, down to rock bottom. There we can shine a light and identify the institutions, political structures and social constructs that dis-value (meaning, rendering something nonexistent, as opposed to simply placing it at a lower place on a hierarchy) the vernacular, the dignity of subsistence-oriented communities and, as Dr. King noted, place “profits before people”.

Wednesday, July 11, 2007

From the Andes to Appalachia (Knoxville, Tn./ 7-11-07)

"We have embodied our world view in our institutions and are now their prisoners."

More soon...